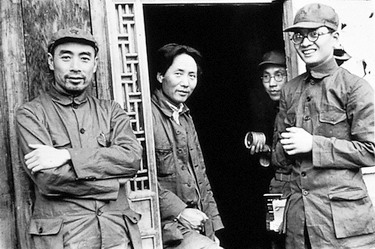

Fellow travelers: Zhou, Mao and 2 revolutionaries I never heard of in Shaanxi, 1937

I spent most of March in Asia and trying to figure out China. To understand the present, you have to understand the past, so I turned to The Search For Modern China, by Jonathan Spence of Yale, which seems to be standard fare for undergrad history surveys. It was a great start, although I wished he had given his analysis of the whys as well as the who, what, when, where, despite the political sensitivities when talking about modern China.

Here is a quick summary mixed with a few conclusions and speculations.

The history of China seems to be a cycle of a strong leader and faction taking over the country, ruling it for generations as a dynasty, then decaying, and eventually getting supplanted by a new dynasty (or a period of civil war and chaos) when they get too weak and corrupt to centrally manage a huge country,

China is a big country, the size of the United States, but 4+ times the population, ie North America plus Western Europe plus most of Latin America. The populated areas are easy to get around through the river systems and flat plains, so anyone who took over would strategically want control all the way to the oceans in the east, mountains in the southwest, and vast deserts in the northwest in order to be safe from internal and external enemies. To the north, fertile land and the reach of the Han people peter out, so a wall may have seemed like a good idea. To lead China, so vast and diverse, is to be a very strong leader, or a very insecure one, or both.

Despite the vast size, and language and cultural differences which are similar to the differences between Italy and Britain, uniting China seems to have been regarded as a desirable thing, as the somewhat fluidly defined 'Han' people seem to have forged a common political and cultural identity for a large part of recorded history. In this they are similar to Indians, who have possibly even more vast language, cultural, and also racial and caste divisions, and yet share a common identity as Indians.

The Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) built the Forbidden City and the Great Wall. Their peak is seen as a time when China seemed to lead the world. But they weakened and turned inward, burning all their ships, and restricting contacts with foreigners who came near.

In 1644 the Ming fell to invaders from Manchuria who took up residence in the Forbidden City and appointed themselves the Qing (pronounced Ching) dynasty. The Mings and previous emperors had generally been content to make the Koreans, Vietnamese, Tibetans and others into 'tributary states' who were under Chinese influence but not ruled from Beijing. But the Manchus, already an ethnic minority ruling the Han, didn't feel inhibited from incorporating additional ethnic groups and extended the borders of China proper into Tibet, Mongolia, and Central Asia. In today's Chinese schoolbooks, the 'tributary state' distinction is glossed over, and historical maps show that Tibet and Central Asian Xinjiang have always been part of China. (In the now disputed Ryuku islands, people sometimes paid tribute to both China and Japan. When the Middle Kingdom's ships were sighted, the locals would hide signs of the Japanese and pay the necessary respect and tribute until the Chinese were back over the horizon.) The current 'Han-ification' of Tibet and Xinjian seems unrelated to any strategic or economic benefit (perhaps there is some mineral potential), and more a matter of pride in restoring the maximum extent of the Qing empire.

While the Mings were turning inward and decaying, Europe entered a turbulent but dynamic phase, took the inventions of gunpowder, paper and printing which originated in China, and took them to a new level. It is interesting to speculate on why Europeans explored the world and improved technology and China did not, but certainly intense competition between rival states provided strong evolutionary incentives, and the Christian schism led to questioning and upending of traditional relationships. Central control, Confucian conservatism, and the challenges of empire may have played a role in China in not encouraging too much individual and creative thinking (and possibly the current CCP feels the same, wanting educated technocrats who don't seek too much change).

Starting from the 1500s, Europeans became big explorers and traders with China. The Portuguese were tolerated at Macau from the 1500s after they did the Mings a favor and killed off local pirates. The British wanted porcelain, silk, tea, and spices, but the Chinese were highly resistant to any imports. This was highly inconvenient, and had major economic repercussions as British gold and silver were used up to buy Chinese goods, leading to tight money. It led the East India Company to an intensive program to grow tea in India using seeds imported from China (ironically, after heroic efforts they found local Indian varieties like Darjeeling grew better and where quite marketable). It also led to growing opium in India and trading it with China, which successfully stopped the outflow of gold and silver.

China now had a problem with opium addiction and balance of payments, and tried to stamp out the opium trade. In 1839, the crafty and competitive independent traders who had entered China after Britain ended the East India Company's China trade monopoly managed to successfully maneuver Britain to war with China, in order to open trade in opium and other products. A half-hearted defense of Britain: there were politicians whose initial reaction was, if China doesn't want opium, don't sell them opium. However, they were no match for the opium traders' ability to stoke political support through judicious application of funds and newspaper propaganda, and their ability to goad the nonplussed Chinese into attacks on persons and property which the British felt 'must not stand', as they say today.

Humiliation ensued for the Chinese, the ceding of Hong Kong island to the British, and the start of a cycle which would continue for the next 90 years. Western commercial exploitation would expand until it met Chinese resistance, which would be a pretext for further military humiliation, taking more land and commercial rights.

Even the colonies got infrastructure to the extent it served commercial exploitation, and legal and institutional frameworks. The Chinese got opium, the sacking of their palaces, removal of antiquities, and 'extraterritoriality', where foreigners were not subject to Chinese law. (In defense of the West, the Chinese did not have a remarkably transparent legal system and had developed a habit of summarily executing accused Westerners.)

In street markets in Hong Kong, vendors display a fish and cleverly chop out and sell pieces in such a way as to inhumanely keep the fish alive and fresh as long as possible. That's how the the French, Americans, Germans, and Japanese carved up China. The amazing thing is that the Qing dynasty actually survived as long as 1911 despite their own ineptitude, conflicts with foreigners, and internal rebellion. In one bizarre episode, a pseudo-Christian religious movement, the Taiping Rebellion held Nanking and surrounding areas for 11 years, until the Western powers helped clean them out after they threatened Shanghai. What regime can survive if it can't keep foreigners and weird cults taking over parts of its heartland?

In the early 1900s the Qing attempted to reform in the direction of constitutional monarchy, but the result was unrest and they were forced out - a lesson surely not lost on 20th and 21st century leaders. But it is sometimes easy to get rid of the old order but not easy to build a new one - the Nationalist government under Sun Yat-sen quickly lost control, and provinces split off under their own leaders and generals/warlords. In 1919 China suffered another disastrous humiliation, when despite sending hundreds of thousands of laborers to Europe to free up Allied troops for fighting duty, and having believed they had a deal for the return of German concessions and industries, the Allies instead gave them to the Japanese in some sharp dealing.

A period of intellectual self-searching followed. The Communist Party was founded in 1922. It received much support from the Soviet Union, and many members studied abroad, in Russia as well as other countries - Deng Xiaoping studied in Paris and Moscow. The Communists allied with Sun Yat-sen and the Nationalists to try to create a united China free from foreign domination. However, Sun Yat-sen died in 1925, and Chiang Kai-Shek, a virulently anti-Communist military leader, took over. After the Nationalists and Communists cooperated to bring a large area under Nationalist control, they predictably fell out. The Nationalists were able to expel the Communists from most of the areas they controlled.

Chiang was brutal, inept, and corrupt. He ascended to leadership through assassination, allying with warlords and underworld figures, and a convenient marriage into Sun Yat-sen's family. On one occasion, the Nationalists broke a Shanghai strike by calling a meeting of the strikers, parading the strike leaders on stage, and shooting them in front of strikers. Nor was he the best friend of commercial interests, targeting them for funds he was perpetually short of.

Chiang followed a strategy of appeasing the Japanese and trying to annihilate the Communists and unite the country. The Communists retreated to an enclave they ruled as the Jianxi Soviet. Chiang encircled them and their survival there appeared in doubt. 100,000 of them broke out, abandoning women, children, and the infirm, and fled Chiang's pursuing army for over a year, losing 90% of their number. Chiang had them encircled again in Shaanxi. But in the meantime the Japanese were becoming increasingly aggressive. In the 'Xian Incident' of 1936 some of Chiang's allies arrested/kidnapped Chiang and pressured him to stop fighting the Communists and unite against the Japanese. After he did, he was soundly defeated and bottled up in Chungqing, and the Japanese used it as an excuse to take over more of China.

The US assisted Chiang unofficially before Pearl Harbor and officially after, but little was accomplished beyond pinning down a Japanese army. Chiang drafted something like 14m conscripts, 10% of whom died of malnutrition and disease before combat, and an additional 34% deserted. Westerners reported conscripts with distended bellies being led to the front lines tied together like chain gangs. Meanwhile, without US assistance, Mao emerged as the Communist leader, and was able to consolidate and effectively govern the small backwaters under Communist control, and resist the Japanese. The US considered giving assistance to Mao, it went all the way to Roosevelt, but Chiang nixed the idea. Of course, all the old China hands involved in those discussions ended up purged and disgraced as Reds in the McCarthy era.

After the Japanese defeat, the US tried to facilitate national reconciliation, sending Marshall to China, but it was a nonstarter for Chiang and would undoubtedly have been a tactical maneuver for Mao. The US sensibly decided to cut Chiang loose. Inevitably, the economy and currency collapsed, as did the defense against Mao. The Nationalists fled and holed up in Taiwan.

After the Communist takeover, while there was violence against landowners and redistribution of land, they appear to have been fairly enlightened at first. When the Korean War broke out, Mao agreed to a military alliance with the USSR and they fought the US and Koreans. Although China initially routed the 'UN forces', and occupied Seoul, the US rallied, and despite losing about 50,000 dead, the Chinese lost an untold multiple of that number.

Still, in 1957 the Communists had reason to feel proud of what they accomplished and Mao made a speech soliciting increased openness and freedom of speech in the 'Hundred Flowers' campaign. When the resulting criticism of the Communists was harsh and hit a bit close to home, a pivot to an 'Anti-Rightist' campaign resulted in all the critics going to jail, labor camps and re-education - a bit of a rope-a-dope, planned or otherwise, to curb dissent. By the time Mao's speech was published, it had been conveniently edited to invite only constructive criticism.

Realizing after failing to prevail in Korea that there was some catching up to do, Mao launched a campaign called the 'Great Leap Forward,' involving full collectivization, massive industrial investment, and, inexplicably, small local 'backyard steel furnaces'. Having learned their lesson of the 'Hundred Flowers', local leaders did not voice any misgivings they may have had, but competed to report immense crops and steel production. The result was a large quantity of useless poor quality steel, massive resource misallocation, and exports of grain while the country endured famine in which tens of millions died.

The brief alliance with the Soviets fell apart. Possibly Mao thought Khruschev was a sellout with his notions of peaceful co-existence with the West and repudiation of Stalin. Possibly the Russians thought Mao was a loose cannon who would not toe Moscow's line, and they ultimately reneged on helping China build the atomic bomb. (Blueprints shredded by expelled Russian advisers were reassembled and reportedly speeded up China's 1964 nuclear test.)

Mao's influence initially waned after the disastrous Great Leap Forward and the more pragmatic technocrats such as Deng tried to get things back on track. However, from 1966, Mao and a faction of hangers-on and enablers pushed back in the form of the Cultural Revolution, urging grass roots radical Communism and attacks on technocrats as elitist capitalist roaders. The radicals got out of control, and ended up killing intellectuals, sending those most capable of rebuilding China to labor camps, destroying much of the cultural heritage Westerners hadn't carted off, and gutting all of the institutions from universities to courts to financial and economic management.

Mao appears to have been a great mass campaigner, but when his time came to govern, all he seemed to know how to do was mass campaigns, eventually against his own revolution. In leading the revolution, he was aided by an instinct for survival and ruthlessness, but also a sure-footed common touch for the needs and aspirations of rural China. In power, he ruthlessly betrayed the peasants in the push for collectivization and industrialization, purged former allies and critics, and ended up out of touch and surrounded by people who told him what he wanted to hear. In a bizarre and ironic twist, the Cultural Revolution destroyed China's institutions, taught a generation of youth to think independently and skeptically of the top leaders, and created a blank slate to rebuild, helping pave the way for modern China.

After Mao died in 1976, the country was a shambles. He had appointed a successor, but Mao's political legacy unsurprisingly faded pretty quickly once he died, and Deng, a leader of the pragmatists and technocrats was able to take over and consolidate power. He started the 'Four Modernizations' (economy, agriculture, technology, and defense), let farmers keep some of what they produced, let people start small enterprises, and launched greater capitalist experiments in the 'Special Economic Zones.' As a sop to conservatives, they were initially limited to 'bird cage' provinces where they could be managed isolated from the rest of the socialist enterprise.

In the 80s, rural China made huge strides in poverty reduction. Many of China's most dynamic enterprises came out of rural China due to grass roots reform. The SEZs were also successful but massive urban change took a long time to take off. In 1989, amid economic difficulties, protests grew for 'the fifth modernization' (political freedom), followed by the Tienanmen massacre. It's instructive that a month of massive urban democracy demonstrations did not bring about much national revolt in the countryside; In fact, after local military were reluctant to intervene, Deng called up rural provincial troops who snuffed out the protests.

After 1989, the reformer Zhao Ziyang was purged and the 'Shanghai Clique', focused on industrial policy and urban development, was brought to power. The focus shifted from grass roots reform to foreign direct investment, state owned enterprises, export-driven growth, industrialization and urbanization. Western banks like Goldman Sachs were brought in to take sketchy and fragmented state-owned assets like 'China Mobile' and turn them into listed 'national champions' theoretically subject to international standards and market discipline. While these policies have been undeniably successful, rural China has suffered from the focus on urban development and top-down industrial policy, diminished subsidies and higher taxes, and corrupt leadership. Illiteracy has actually increased as tuition fees rose, parents migrated for better opportunities or because they had no choice, and kids had opportunities to go to work. Post-1989 rural stagnation is ironic, since rural support helped bring the CCP to power and remain there after Tiananmen.

The post 2009 financial crisis has brought a new, still unclear phase. Faced with a steep drop in exports, China undertook a massive stimulus to build infrastructure, and promised to take steps to reduce reliance on exports and boost domestic consumption. Less promisingly, the financial crisis reduced the prestige of 'international' accounting standards and market discipline, and banks and state owned enterprises were subjected to Party mandates to keep the economy going. As the world economy has recovered, China has been overheating. But the stimulus projects like huge railway and residential construction seem unlikely to pay off with actual cash flows, which will lead to stress on an immature, politicized corporate and financial system.

After 60-plus years, China has in large measure achieved unity, global respect, economic strength, and lifted most of the country out of extreme poverty. As a dynasty, it's a very respectable showing after a quick start and a very rocky consolidation period. Someone who was born in 1930 has experienced an almost unbelievable amount of tumult and change. That rapid change has resulted in tremendous dislocations, social stress, and weak institutions. There is no shortage of ambition or political will to take tough steps. But desire for real liberalization is absent. Since the CCP went all-in in 1989 and drew a hard line on political liberalization, the apparent choice then becomes accepting a strong ruler, or risking a return to the chaos that preceded 1949.

The question becomes how far this dynasty can grow before it outpaces the ability of strong central rulers to stay on top of it, and weak governance, corruption, and frustrated desires of the population lead to decay and unrest. China has seen change and tumult postwar Westerners can barely imagine. And of course, since China is now at the center of massively unbalanced patterns of trade, finance, investment and consumption, whatever happens next will have a huge impact around the world.

Possible further reading:

The Search for Modern China, Jonathan D. Spence

China and Europe, 1500-2000 and beyond: What is Modern?, Ken Pomeranz and Bin Wong, Columbia University

Mao Zedong and China's Revolutions: A Brief History with Documents, Timothy Cheek

The Private Life of Chairman Mao: The Memoirs of Mao's Personal Physician Dr. Li Zhisui, Dr. Li Zhisui

Prisoner of the State: The Secret Journal of Premier Zhao Ziyang, Zhao Ziyang (Author), Adi Ignatius (Editor)

Red Star over China: The Classic Account of the Birth of Chinese Communism, Edgar Snow

China Road: A Journey into the Future of a Rising Power, Rob Gifford